Augmented reality for stroke rehabilitation during COVID-19 | Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation | Full Text

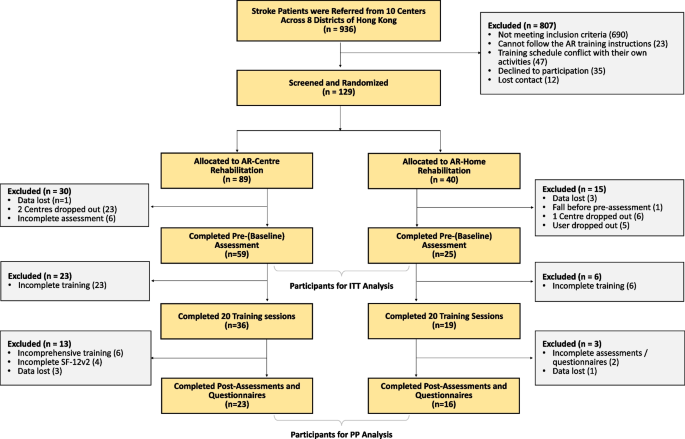

The study was an assessor-blind, randomized controlled trial and was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee. Participants were recruited through 10 local public rehabilitation centres, which are distributed over 8 different districts of Hong Kong. Written informed consents were obtained from participants prior to the enrollment.

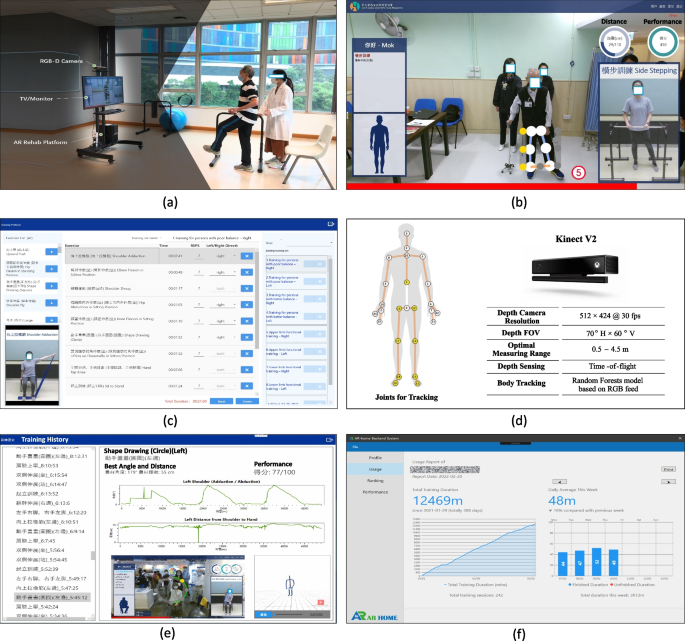

The AR rehabilitation system for virtual training. a System architecture and training scene; b Training in progress; c Training plan customization; d Body tracking joints and the Kinect sensor; e Real-time report; f Training statistics

Chronic stroke survivors were selected with inclusion criteria: (1) age between 18 to 90 years who are diagnosed with ischemic brain injury, intracerebral haemorrhage shown by magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography after the onset of stroke; (2) with motor impairment in upper-limb, lower-limb, and/or balance; (3) have no or mild spasticity on the lower-limb or upper-limb assessed by Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS \(\le\) 2); and 4) have sufficient cognition to follow the instructions provided by the therapists and the computer. The exclusion criteria included: (1) any additional medical or psychological condition that would affect their ability to comply with the study protocol, e.g., a significant orthopaedic or chronic pain condition, major post-stroke depression, epilepsy, artificial cardiac pacemaker/joint; (2) have severe shoulder/arm or hip/knee contracture/pain and; (3) Pregnant women. Potential participants were referred by their doctors or therapists, and screened at the nearest centres. A brief tutorial of using the AR training system was given, and then the participants were required to use the system as a test to see if they can follow the instructions and complete the exercises independently. Participants who failed in the test were excluded.

Randomization and blinding

Randomization of group allocation occurred before the baseline assessment at centre level, in the way that participants who met the eligibility were first assigned to the nearest centre, and then randomly allocated to the AR-Centre or AR-Home group with a ratio of 1:1. The assignment of centre was due to the consideration of their limited mobility and the government’s regulations for prevention and control of disease during COVID-19. Baseline assessments were conducted after the assignments. This study was blinded at two levels. For the general objective of investigating whether AR rehabilitation worked, it was single blinded to assessors, because it was easy for recruiters, therapists and patients to see the difference from the usual care and was thus impossible to make this objective blind [34, 39, 48]. All assessors obtained their qualifications for the clinical assessments before joining the study. Furthermore, the objective in this study was not only to answer a question of whether AR training worked, but also to answer a more practical question of HOW it worked in a real and pandemic setting. The hypothesis was to use an integrated trial of human and virtual trainers. This was blinded to all recruiters, assessors, therapists, and patients.

CONSORT diagram of this study. Centres dropped out because their services were limited due to the government’s regulation in the pandemic. Users dropped because of quarantine or not being able to return to Hong Kong. Assessment data were lost because the regular handover process was disrupted in the pandemic

CONSORT diagram of this study. Centres dropped out because their services were limited due to the government’s regulation in the pandemic. Users dropped because of quarantine or not being able to return to Hong Kong. Assessment data were lost because the regular handover process was disrupted in the pandemic

Each participant received a standard trial consisting of 20 training sessions (2–5 sessions per week, 120 min per session) in consecutive 4–10 weeks. Each session consisted of 2–10 exercises selected by the trainer from a pool of 46 exercises. The selected exercises were tailored based on the participant’s condition and progress. The exercise pool was designed as much comprehensive as possible to cover the upper-limb (22 exercises) and lower-limb (7 exercises) motor functions, balance ability (11 exercises), or/and coordination (6 exercises). Each exercise was with a duration ranging from 3 to 23 min, and was determined by a set of parameters that can be adjusted to the individuals dynamically according to the participant’s performance.

The training was delivered in an integrated manner of a human PT/OT/Assistant trainer (called human trainer hereafter) and a AR rehabilitation system (called virtual trainer hereafter).

The two groups of AR-Centre and AR-Home were designed with different configurations of trainers to study the best way to integrate the AR training into usual care.

AR-Centre group: The training was conducted at the rehabilitation centres following the same procedure as their regular usual care, with 3/4 of each session delivered by a human trainer and the rest of 1/4 delivered by a virtual trainer.

AR-Home group: The training was conducted mainly at home (3/4 of each session) and delivered by the virtual trainers. However, at the beginning of each session, there was a short (half an hour or 1/4 time of a regular usual care session) in-centre/at-home training delivered by human trainers to make the participants familiar with the subjects and procedures. To this end, upon the recruitment, a human trainer was randomly assigned to a participant for tailoring her training plan according to the baseline assessment. While the participant was taking the training at home, the human trainer could monitor the training process remotely. Reports of the training were sent to the human trainer on a weekly basis. The human trainer could adjust the training plan based on the participant’s performance.

The AR rehabilitation system for virtual training

As shown in Fig. 2, the AR rehabilitation system consists of a Microsoft Kinect V2 RGB-D camera for sensing the body movements of the patients, a TV/Monitor for displaying instructions and giving real-time assessments, and an AR rehabilitation software platform which has been implemented with the latest arts of AR and AI technology for delivering the training. The system is installed on a portable TV frame (NB MOUNT AVA 1500-60-IP) and is capable of communicating with our rehabilitation sever for synchronizing the latest training materials (videos, exercises, schedules, and training reports).

The system is able to deliver the exercises following the same procedure as in the usual care. The exercises performed by therapists are prerecorded. Every exercise starts by a brief voice introduction followed by a video demonstration with detailed steps. The participant will then follow the steps to do the exercise. Her body movements will be sensed into 3D skeletons, on the basis of which parameters such as the centre of Mass-COM, body parts, joint angles, reaching distances, speed and directions of the motions, and trajectory are evaluated. At the end of exercise, immediate feedback will be given as a report with the performance details and compared with her early performance. In addition, the participant can review her performance through the skeleton videos recorded during the exercise to locate the exact steps which she needs to pay more attention for further improvement. The performance details with the skeleton videos are synchronized to the cloud so that the human trainer could review her performance and adjust her training plan accordingly.

Participants received the pre-assessment within two weeks before the first training, and the post-assessment within two weeks after the last training. Assessments were conducted at centres for the AR-Centre group and at homes for the AR-Home group.

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome measures focused on the motor function, balance, and functional ambulatory, which include (1) Fugl-Meyer Assessment with Upper Extremity and Lower Extremity (FMA-UE and FMA-LE); (2) Berg Balance Scale (BBS); (3) Functional Ambulation Category (FAC).

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures included the assessments of (1) Quality of life (QOL): physical and mental health using the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12v2); (2) User experience (UX) using questionnaires (designed based on UEQ-S); and (3) Activities of Daily Living (ADL) using Barthel Index (BI).

To evaluate the human effort required to deliver the training, the time of human training, the time of virtual training, the ratio of human training over the total training time, the number of human trainers required for each participant were calculated. The in-centre contact rate was calculated based on the numbers of PTs, OTs, training assistants, supporting staff, teammates the participant encountered at the centre. The numbers varied from centres and individuals. We used the numbers estimated by the PTs/OTs/Assistants and calculated the average across centres.

In addition, to study the clinical significance, we identified participants who were with improvement exceeding the Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) or Minimally Detectable Change (MDC), on the basis of which we used the proportion of participants with clinical performance improvement as a supplementary measure for the efficacy of the training. More specifically, MCIDs reported in [49,50,51] were used for FMA-UE, BI, and SF12v2 PCS, and MDCs reported in [52], [53] were used for FMA-LE and BBS. For SF12v2 MCS, we used the \(10\%\) of the maximum as the threshold, because there is no MCID/MDC reported in literature. Similarly, for FAC, the clinical significance was evaluated by whether a participant of limited mobility (baseline FAC\(<4\)) become an independent walker (post-assessment FAC\(>=4\)) [54].

Statistical analysis

The normality of all demographic, clinical variables was tested by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov method or Shapiro-Wilk method and histogram inspection. To assess the group differences on the baseline data, we used Independent Sample t tests for numerical data with a normal distribution, and Mann-Whitney U tests for data with a skewed distribution. For categorical data, we used Pearson Chi-square tests or Fisher Exact tests. To assess the differences between pre- and post-assessments, Paired t-test was used for data with a normal distribution, and Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks tests were used for data with a skewed distribution.

All outcomes measures were analyzed using both per-protocol analysis (PP) and intention-to-treat principle (ITT), and missing data were dealt with the last observation carried forward method. All outcomes aim to evaluate whether the results demonstrate feasibility of assistance with virtual rehabilitation when integrated into the usual care in a real-world pandemic setting. Statistical results were reported with the effect size in confidence interval of \(95\%\) (95% CI). Two-tailed levels of significance at 5% was used.

This content was originally published here.