AI timelines: What do experts in artificial intelligence expect for the future? – Our World in Data

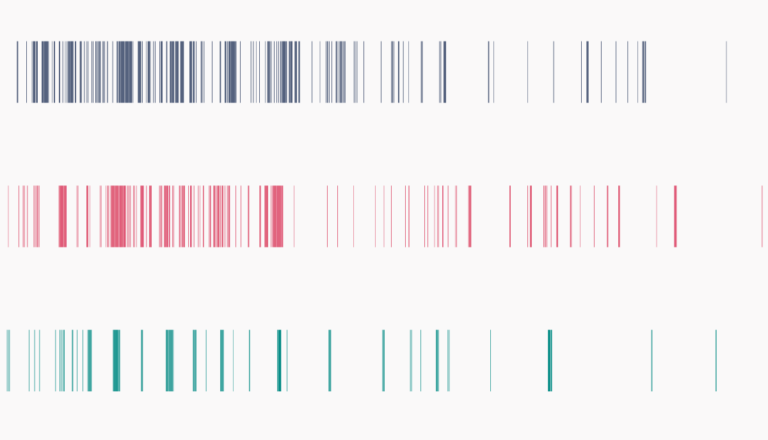

The three cited AI experts surveys are:

The surveys were conducted during the following times:

The surveys differ in how the question was asked and how the AI system in question was defined. In the following sections we discuss this in detail for all cited studies.

The study by Grace et al. published in 2022

Survey respondents were given the following text regarding the definition of high-level machine intelligence:

“The following questions ask about ‘high-level machine intelligence’ (HLMI). Say we have ‘high-level machine intelligence’ when unaided machines can accomplish every task better and more cheaply than human workers. Ignore aspects of tasks for which being a human is intrinsically advantageous, e.g., being accepted as a jury member. Think feasibility, not adoption. For the purposes of this question, assume that human scientific activity continues without major negative disruption.”

Each respondent was randomly assigned to give their forecasts under one of two different framings: “fixed-probability” and “fixed-years.”

Those in the fixed-probability framing were asked, “How many years until you expect: A 10% probability of HLMI existing? A 50% probability of HLMI existing? A 90% probability of HLMI existing?” They responded by giving a number of years from the day they took the survey.

Those in the fixed-years framing were asked, “How likely is it that HLMI exists: In 10 years? In 20 years? In 40 years?” They responded by giving a probability of that happening.

Several studies have shown that the framing affects respondents’ timelines, with the fixed-years framing leading to longer timelines (i.e., that HLMI is further in the future). For example, in the previous edition of this survey (which asked identical questions), respondents who got the fixed-years framing gave a 50% chance of HLMI by 2068; those who got fixed-probability gave the year 2054.14 The framing results from the 2022 edition of the survey have not yet been published.

In addition to this framing effect, there is a larger effect driven by how the concept of HLMI is defined. We can see this in the results from the previous edition of this survey (the result from the 2022 survey hasn’t yet been published). For respondents who were given the HLMI definition above, the average forecast for a 50% chance of HLMI was 2061. A small subset of respondents was instead given another, logically similar question that asked about the full automation of labor; their average forecast for a 50% probability was 2138, a full 77 years later than the first group.

The full automation of labor group was asked: “Say an occupation becomes fully automatable when unaided machines can accomplish it better and more cheaply than human workers. Ignore aspects of occupations for which being a human is intrinsically advantageous, e.g., being accepted as a jury member. Think feasibility, not adoption. Say we have reached ‘full automation of labor’ when all occupations are fully automatable. That is, when for any occupation, machines could be built to carry out the task better and more cheaply than human workers.” This question was asked under both the fixed-probability and fixed-years framings.

The study by Zhang et al. published in 2022

Survey respondents were given the following definition of human-level machine intelligence: “Human-level machine intelligence (HLMI) is reached when machines are collectively able to perform almost all tasks (>90% of all tasks) that are economically relevant better than the median human paid to do that task in 2019. You should ignore tasks that are legally or culturally restricted to humans, such as serving on a jury.”

“Economically relevant” tasks were defined as those included in the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) database. O*NET is a widely used dataset of tasks carried out across a wide range of occupations.

As in Grace et al 2022, each survey respondent was randomly assigned to give their forecasts under one of two different framings: “fixed-probability” and “fixed-years.” As was found before, the fixed-years framing resulted in longer timelines on average: the year 2070 for a 50% chance of HLMI, compared to 2050 under the fixed-probability framing.

The study by Gruetzemacher et al. published in 2019

Survey respondents were asked the following: “These questions will ask your opinion of future AI progress with regard to human tasks. We define human tasks as all unique tasks that humans are currently paid to do. We consider human tasks as different from jobs in that an algorithm may be able to replace humans at some portion of tasks a job requires while not being able to replace humans for all of the job requirements. For example, an AI system(s) may not replace a lawyer entirely but may be able to accomplish 50% of the tasks a lawyer typically performs. In how many years do you expect AI systems to collectively be able to accomplish 99% of human tasks at or above the level of a typical human? Think feasibility.”

We show the results using this definition of AI in the chart, as we judged this definition to be most comparable to the other studies included in the chart.

In addition to this definition, respondents were asked about AI systems that are able to collectively accomplish 50% and 90% of human tasks, as well as “broadly capable AI systems” that are able to accomplish 90% and 99% of human tasks.

All respondents in this survey received a fixed-probability framing.

The study by Ajeya Cotra published in 2020

Cotra’s overall aim was to estimate when we might expect “transformative artificial intelligence” (TAI), defined as “ ‘software’… that has at least as profound an impact on the world’s trajectory as the Industrial Revolution did.”

Cotra focused on “a relatively concrete and easy-to-picture way that TAI could manifest: as a single computer program which performs a large enough diversity of intellectual labor at a high enough level of performance that it alone can drive a transition similar to the Industrial Revolution.”

One intuitive example of such a program is the ‘virtual professional’, “a model that can do roughly everything economically productive that an intelligent and educated human could do remotely from a computer connected to the internet at a hundred-fold speedup, for costs similar to or lower than the costs of employing such a human.”

When might we expect something like a virtual professional to exist?

To answer this, Cotra first estimated the amount of computation that would be required to train such a system using the machine learning architectures and algorithms available to researchers in 2020. She then estimated when that amount of computation would be available at a low enough cost based on extrapolating past trends.

The estimate of training computation relies on an estimate of the amount of computation performed by the human brain each second, combined with different hypotheses for how much training would be required to reach a high enough level of capability.

For example, the “lifetime anchor” hypothesis estimates the total computation performed by the human brain up to age ~32.

Each aspect of these estimates comes with a very high degree of uncertainty. Cotra writes: “The question of whether there is a sensible notion of ‘brain computation’ that can be measured in FLOP/s—and if so, what range of numerical estimates for brain FLOP/s would be reasonable—is conceptually fraught and empirically murky.”

For anyone who is interested in the question of future AI, the study of Cotra is very much worth reading in detail. She lays out good and transparent reasons for her estimates and communicates her reasoning in great detail.

Her research was announced in various places, including the AI Alignment Forum: Ajeya Cotra (2020) – Draft report on AI timelines. As far as I know the report itself always remained a ‘draft report’ and was published here on Google Docs (it is not uncommon in the field of AI research that articles get published in non-standard ways). In 2022 Ajeya Cotra published a Two-year update on my personal AI timelines.

Other studies

A very different kind of forecast that is also relevant here is the work of David Roodman. In his article Modeling the Human Trajectory he studies the history of global economic output to think about the future. He asks whether it is plausible to see economic growth that could be considered ‘transformative’ – an annual growth rate of the world economy higher than 30% – within this century. One of his conclusions is that “if the patterns of long-term history continue, some sort of economic explosion will take place again, the most plausible channel being AI.”

And another very different kind of forecast is Tom Davidson’s Report on Semi-informative Priors published in 2021.

This content was originally published here.